Monday, July 22, 2013

Cosmos is coming back

Last year PBS dusted off Friedman's Free to Choose series with a three-part update about how his ideas look today titled Testing Milton Friedman.

Well, now this has been revealed:

I remember about five years ago before I had heard of Neil deGrasse Tyson that Bill Nye would be perfect for a Cosmos reboot. While I'm sure he'd do a great job, NdGT is clearly the best person alive to host this. He captures the joy of science better than anyone else, and he's an astronomer to boot.

I love me some economics, but man, astronomy has such better visuals. I'll take a super nova over Brad Delong's face any day.

Read more...

Monday, January 9, 2012

Adam Smith vs. Friedrich August von Hayek

This weekend I started reading the newly-released volume two of Yoram Bauman's Cartoon Introduction to Economics that shared an Adam Smith quote from Book IV of the Wealth of Nations:

What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom.This idea started the classical view of economics, that running a country is like running a household. However, seeing it in this cartoony context caused my mind to contrast it with a famous Friedrich Hayek quote from The Fatal Conceit:

Part of our present difficulty is that we must constantly adjust our lives, our thoughts and our emotions, in order to live simultaneously within the different kinds of orders according to different rules. If we were to apply the unmodified, uncurbed, rules of the micro-cosmos (i.e. of the small band or troop, or of, say, our families) to the macro-cosmos (our wider civilisation), as our instincts and sentimental yearnings often make us wish to do, we would destroy it. Yet if we were always to apply the rules of the extended order to our more intimate groupings, we would crush them. So we must learn to live in two sorts of world at once.Can I fit both of these ideas into my head without breaking something? I don't think I can. One of my favorite criticisms of communal societies and small-scale attempts at collectivism is that it doesn't scale. If that's true, how can I absorb Adam Smith's wisdom that a government should tighten its belt when times are tough, just like a household should?

Read more...

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

We must put a price on human lives

I don't know how many times I've heard people speak out against institutions they claim puts a price tag on human lives. Both anti-corporation and anti-government activists accuse their foes of valuing money more than humanity.

I don't know how many times I've heard people speak out against institutions they claim puts a price tag on human lives. Both anti-corporation and anti-government activists accuse their foes of valuing money more than humanity.When a car company declines to install a safety device, that's putting a price on human lives. During the 2008 debates Sarah Palin declared a national health care program would use "death panels" to decide which lives are worth saving.

But coming at these issues from the economic mindset, the real scandal would be car companies that install every safety device possible and the horror of a national health care program would not be in having death panels, it would be in not having them.

This principle of only saving lives if the cost is low enough is well accepted with most people, they just don't realize it. It takes three different forms I will focus on in decreasing order of popularity.

Risking lives to save more lives

At the cost of a few lives, you will save many more lives.

This is straight-up utilitarianism. If three hundred people have a deadly disease that will kill them in less than a week, and you have a drug that will cure it outright but also kill two or three of the patients, you give it to them.

This is a no-brainer. At the cost of a few lives you have saved hundreds. You're exposing people to a little risk to avoid a bigger risk. This is the idea behind vaccines, airbags, triage and a lot of other things. You're trading risk for risk, and on the average you win. There is little controversy when people properly understand what the stakes are.

Risking lives to save quality of life

At the cost of a few lives, you will improve the quality of many lives.

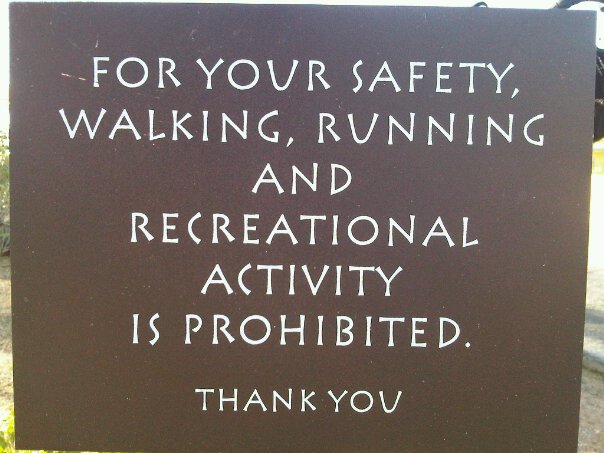

There are things that anyone can do to lower their risk of a specific cause of death. As oncologist Dr. David Gorski wrote, there's a lot of danger in riding an automobile, playing sports and even swimming. Foregoing these activities will increase safety, but is it worth it? What about eating salads for every meal, wearing a helmet at all times and never leaving the house?

Some of these actions will expose the actor to other risks, such as a weak body, malnutrition or poverty, but the main factor is the quality of life. Lenore Skenazy writes about how the obsession with child safety is ruining childhood on her blog Free-Range Kids. This principle was the focus of my recent piece on invasive searches for airline travelers. Sure, it may eventually save a few lives, but at the cost of harming the quality of millions of lives.

Now some people do think the harm of the TSA searches is worth it for the extra protection we get. I must ask, are they really disagreeing with the principle, or just the price? What if the searches were more invasive? I imagine terrorists would have a difficult time getting weapons on a plane if all passengers were naked and had no carry-ons. Would that cost be worth it too? If not, then they clearly agree with the principle I'm presenting.

Risking lives to save money

At the cost of a few lives, you will save a lot of money.

This is where people start to back away. Philosopher Peter Singer recently wrote that because most people can agree that extending someones life a month for the cost of millions of dollars may not be worth the price, they are therefore open to the idea of rationing health care:

Remember the joke about the man who asks a woman if she would have sex with him for a million dollars? She reflects for a few moments and then answers that she would. “So,” he says, “would you have sex with me for $50?” Indignantly, she exclaims, “What kind of a woman do you think I am?” He replies: “We’ve already established that. Now we’re just haggling about the price.” The man’s response implies that if a woman will sell herself at any price, she is a prostitute. The way we regard rationing in health care seems to rest on a similar assumption, that it’s immoral to apply monetary considerations to saving lives — but is that stance tenable?Milton Friedman made a similar point when asked if its ethical for an automobile company to avoid installing a cheap safety device. He argued that he doesn't know if the cost of the device was worth the limited amount of safety it gave, and it should be up to the customer to decide how much safety they are willing to pay for. At the heart of his response, Friedman said:

Nobody can accept the principal that an infinite value should be placed on an individual life.So in effect, arguing that a company should install a safety device to combat a specific amount of risk is haggling the price of a human life. It is not rejecting the principle.

Never assume your current level of safety is optimal, so that increasing risk is out of the question.

Say there was a device that made your home 100 percent safe from asteroids. Any space-borne rocks that hit your home will be safely deflected each and every time, and at a cost of $12,000 a year. Of course, asteroids do not pose a substantial risk to the public; a person's chances of being injured or killed by an asteroid in a given year is one in 70 million.

But say you already have the device in place and decided to discontinue it's use. You'd save yourself $1,000 each month, but you'd have to accept the principle that you are increasing your chances of an unnatural death in order to save money. You can't get around this fact, and that's what I mean by not assuming your current level is optimal. If it's right to avoid paying a big fee for a small amount of protection, its no different to cut big costs in exchange for a small increase in risk.

That was my point when I wrote that it doesn't matter if hiring more nurses, teachers or soldiers will improve outcomes if it comes at too high cost. It's possible we have too few nurses, teachers and soldiers, and it's also possible we have too many. We should always be open to changing the number we have, even if it means spending more money or lowering our health, test scores or national security.

It's also important to remember the opportunity cost of protecting ourselves from one threat could leave us vulnerable to another. I have added emphasis to something Carl Sagan wrote in The Pale Blue Dot:

Public opinion polls show that many Americans think the NASA budget is about equal to the defense budget. In fact, the entire NASA budget, including human and robot missions and aeronautics, is about 5 percent of the U.S. defense budget. How much spending for defense actually weakens the country? And even if NASA were cancelled altogether, would we free up what is needed to solve our national problems?

Imagine spending all your time collecting crosses, stakes and holy water only to be mutilated by werewolves. Still, buying one more clove of garlic will make you a little bit safer from Dracula. If we sink too much of our budget in one program, we have to neglect others.

Sacrificing life for money at all costs is indirectly sacrificing quality of life and other lives to save specific lives. Those are all costs as well, and money is just a stand-in for the resources that must be sacrificed. Increasing one form of spending too much will cannibalize the rest of the economy and make everyone worse off. The big question is where that line is drawn.

It's clear that its worth saving a human life when the only cost is the effort of throwing a life preserver overboard, and not worth saving at the cost of all the resources of an entire continent. The extremes are easy, but making decisions at the margin is tough. Finding the optimal point is beyond tricky: it's impossible. No one can discover the value of an unspecified person's life, and any number they come up with will be arbitrary.

Protecting lives comes at a cost, be it in terms of sacrificing other lives, the quality of life or money. This is a single principle, not three separate principles, and one must accept or reject them all.

Read more...

Thursday, May 20, 2010

My greatest intellectual influences

- Politics and the English Language by George Orwell. This brilliant essay introduced me to six of the seven rules of writing I live by (the extra one was provided by a high school English teacher - put the focus of the sentence at the beginning, and not the end). In addition, Orwell mocked the blocky, obtuse writing of eggheads - something I have never stopped doing. A companion influence is The Elements of Style by William Strunk and EB White.

- Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond. A research trip to Papua New Guinea for bird physiology lead to Diamond's provocative explanation for international inequality and provides powerful examples of how innovation, trade and specialization all create wealth. I confess to never reading the book and only watching the National Geographic documentary.

- Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt. This taught me the Broken Window fallacy, and it's countless forms. Fallacies have an eternal nature and its important to recognize all their mutations. Companion influences are essays by Frédéric Bastiat; both That Which is Seen, and That Which is Unseen and the satirical Candlemakers' Petition.

- Milton Friedman. His entire body of work is so important to me that it's hard to find a single lecture, essay, book or video to link. Hopefully this 1978 exchange does the trick. There has never been a greater champion for the rights of the individual than Friedman. He taught me that trying to save a society directly will destroy it, while empowering the common man will save the society at large.

- Economics for Dummies by Sean Masaki Flynn. I was concerned I was learning too much of economics from libertarian sources, so I went out of my way to learn the basics from a neutral source. Flynn was the right man for the job - a Keynesian who wasn't shy to call Karl Marx discredited. Flynn reminded me that reasonable people can disagree.

- Pop Internationalism by Paul Krugman. I'm a Krugman hipster - I like his old stuff better. David Henderson called this the best book on trade around. Krugman outlined the case for free trade and dismantled a number of economic fallacies in a short, accessible format. This is a lively book and I still enjoy thumbing through it. A companion influence is Krugman's 1997 article In Praise of Cheap Labor which nailed the moral argument in support of sweatshop labor.

- Cornucopia: The Pace of Economic Growth in the Twentieth Century by J. Bradford DeLong. Originally, I started referencing Krugman and Delong because their status as loud left wingers made my economic points appear stronger and universal. Today I link them because they have produced some amazing work. This essay on how much wealthier we are today, and how hard it is to measure that wealth, is nothing short of astounding. It's easy enough for anyone to read, and absolutely everyone should read it.

- The Demon-Haunted World by Carl Sagan. The best introductory book to scientific skepticism around. Chapter 18, The Wind Makes Dust, taught me to appreciate Yankee ingenuity for what it is: people learning science the moment it becomes practical to their lives. A companion influence is the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe podcast.

- Seanbaby. My favorite internet comedy writer. He shaped my sense of humor and steered me towards appreciating the hokey, the kitschy and the unintentional.

- The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich August von Hayek. This book solidly trounced the concept of central planning. However, it suffers from the strained writing style of Austrian-born Hayek. George Orwell reviewed this book, which tells us he read it. Unfortunately, Hayek couldn't read Politics and the English Language before he wrote this important book; this book predates that essay by two years.

- The Myth of Violence by Steven Pinker. This 20 minute lecture is the ultimate answer to anyone who argues that modern society have brought about an epidemic of violence. Pinker demolishes that idea, shows its quite the opposite and makes a strong case for the peaceful effects of international trade.

- EconTalk hosted by Russ Roberts. I found this podcast when I wanted to find out what economists think of "buy local" campaigns - and boy did I get an answer. Roberts has a constant stream of fascinating and counter-intuitive guests. When I was a kid I always saw intellectual programs as stuffy and dull. I've learned this is seldom the case, and when Roberts invites Mike Munger onto the show I know I'm in for some solid humor as well as economics.

Read more...

Thursday, April 22, 2010

How similar are Carl Sagan and Milton Friedman?

Carl Sagan was a NASA astronomer and science popularizer. Milton Friedman was a Nobel Prize winning economist who spoke to high school students and presidents the exact same way. Neither one was afraid to speak about politics, and they commanded opposite sides of the political spectrum.

Outside of the occasional libertarian, most people I meet respect one of these two intellectual leaders at the most. Carl attracts the left wing student types - most of whom only know Milton as the scapegoat of social activists. Milton, on the other hand, tends to bring in the older conservatives - a lot of whom don't see science as the ultimate source of knowledge.

But today it occurred to me that although their political stances were usually far apart, the two have a lot in common.

First the superficial things:

Both Carl and Milton graduated from Rahway High School in New Jersey. They grew up in Jewish families but became agnostic. Both passionately advocated marijuana legalization.

In January, 1980 PBS started airing Milton's 10 part "Free to Choose" series, which popularized economic science. In September of the same year PBS began broadcasting Carl's 13 part "Cosmos: A Personal Voyage." Both series are still remembered as excellent, accessible presentations on their given topics. Both Carl and Milton worked on their television series with their regular collaborators - their wives.

Most importantly, both Carl and Milton showed the world a contagious enthusiasm for science. Both were science popularizes - a difficult task to accomplish. A poor job can be seen as dry and boring or "dumbing things down." Carl and Milton nailed those topics in a way that's still fun and informative 30 years later.

They share one more important aspect. The world was made much poorer with each of their deaths. Thankfully these public intellectuals were not camera shy and future generations can benefit from their spirited presentations of science. Carl and Milton left the world a much better place than they found it, and one can't help but hear their voices when they read from the texts each one left behind.

Read more...